The research for Acts of Memory took place during my year long Decade of Centenaries artist-in-residence at Trinity Long Room Hub, Trinity College Dublin, 2021-22. There, I observed the team behind the fascinating and ambitious initiative, The Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland (VRTI) at close quaters. This diverse group of historians, conservators, archivists, and computer scientists, were working together with the common goal of creating an innovative digital archive to hold replacements for the records that were once housed in the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) before its tragic destruction during the opening engagement of the Irish Civil War in 1922.

The realisation of the scale of the loss of centuries worth of archival documents, which chronicled the lives of those who lived in Ireland from the 13th Century onwards, stopped me in my tracks.

What effect does losing the traces of a specific history have in the here and now? And more precisely for me, what creative path could I take in response to this cataclysmic event, the aftermath and its recovery?

BOOM! And the future stopped standing in its proper place

As the Virtual Record Treasury team began to recover some of the lost archival material, I reflected on the significance of official records which I saw as serving as gateways to both known and unknown pasts. I watched how carefully the conservators in both National Archives Ireland and the Public Record Office Northern Ireland, partners in the project, restored the fragile documents, some scarred by the fire in 1922 and others just damaged through time. More material continued to be unearthed by the team's extensive catalogue searches in libraries and archives around the world, finding both original and copies of the original material. In the National Archives UK, another partner in the project, medieval material relating to Ireland was shared with the team in Dublin and I began to think about kinship.

What relation would these documents, in digital form, have to the original? Would they be as close as a sibling, a cousin or would they be like a distant cousin where the contact had been lost due to the previous generation dying out? How could this lineage be drawn? Was understanding the path leading to the item's discovery significant? The new Virtual Record Treasury website would have the names, dates and links listed beside the uploaded material, connecting each item to the many and varied institutions where it was found. It would also hold within the image coded information embedded in the digital data itself.

Digital v Real

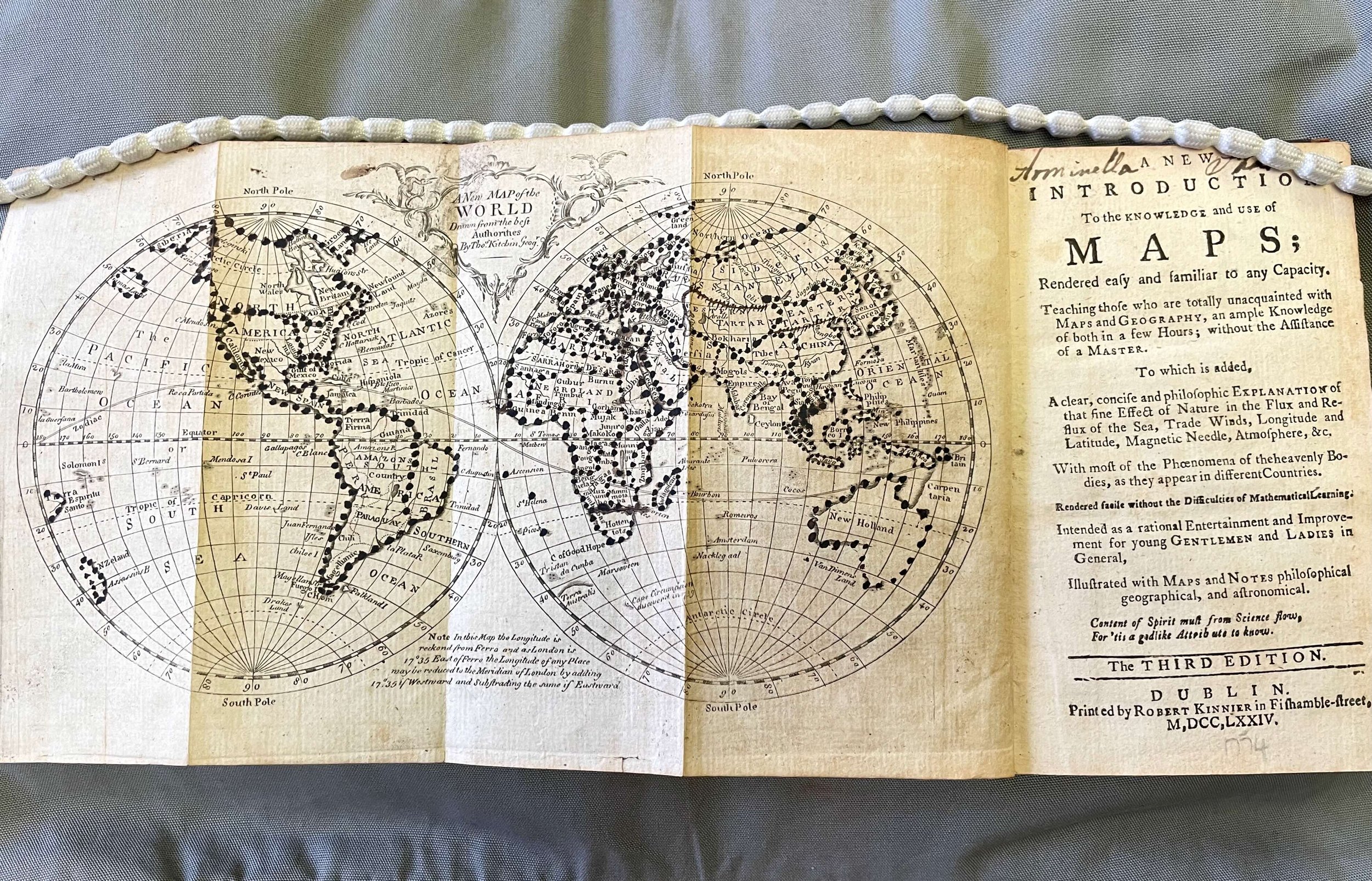

Uncoupled from the sensory experience contained within an original, I find that digital documents come with their own set of physical parameters. I use the magnification function on my keyboard for example to look more closely at the meticulous hand drawn maps depicting county boundaries, town-lands and large estates (with the exact number of trees drawn in a field near a house). The maps of Ireland in digital form (now totalling 8000 available to view online), allow for a different perspective of the landmass, one that I have seen many times before in physical map form, but have never taken the time to really look at.

With the use of my keyboards command + tab function, the pinching movement of my finger and thumb on a track pad, I zoom in and out, up to the top of hills and mountains and down to the shoreline and beyond seeing for what seems like the first time, out to the oceans contours and the topography which I'm told, provides information on the size, shape and distribution of the coasts underwater features. I think about how the maps change through time and how the life that is lived changes over that same time.

From there, I travel in my mind's eye between the real and the digital, back and forth through the copies of ships records documenting exotic cargo coming to Ireland in the 17th Century and imagining the designated wealthy recipients. I make a leap on through time to a memory of my father telling me of his excitement receiving an orange in his Christmas stocking in County Tyrone in December 1940, and I see a boy's hand pulling a brightly coloured, dimpled round ball from inside of a sock, which smells fresh and sweet and whose bitterness makes his face crease up in wrinkles and smiles as he tastes it.

Nothing is lost | everything is found

Echoing writer *Katy Burn's insight that "archives are not static arsenals of information, but sites where various actors negotiate agency, identity, and power," I find myself looking for information in an almost piece meal way. I find a wealth of stories in the records held within a Digest of Cases decided by the Superior and other courts in Ireland, 1894-1918. They describe the circumstances surrounding each scheduled court cases, the plaintiff, the case and the verdict. Here, I find traces of the people's lives that resonate.

As the VRT project progresses, each discovery yields tangible bonds to a physicality that I had thought might not translate to the digital form; Finger prints, pen marks, dog-eared corners, doodles, marks made by accident or deliberately on these official documents, clearly there on the paper before and after scanning and all ingested into the open source platform created by the specialist software engineers. An idea from Walter Benjamin's in his final work 'On the Concept of History, comes to mind:

"A chronicler who recites events without distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accordance with the following truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history."

As I continue to find a path through the lists of found artefacts, it seems to become easier to locate the 'presumed' incidental within the historical timeline. Its as if the archive has undergone a shift in hierarchy, imbuing it with a newfound democratic essence in its digitised form.

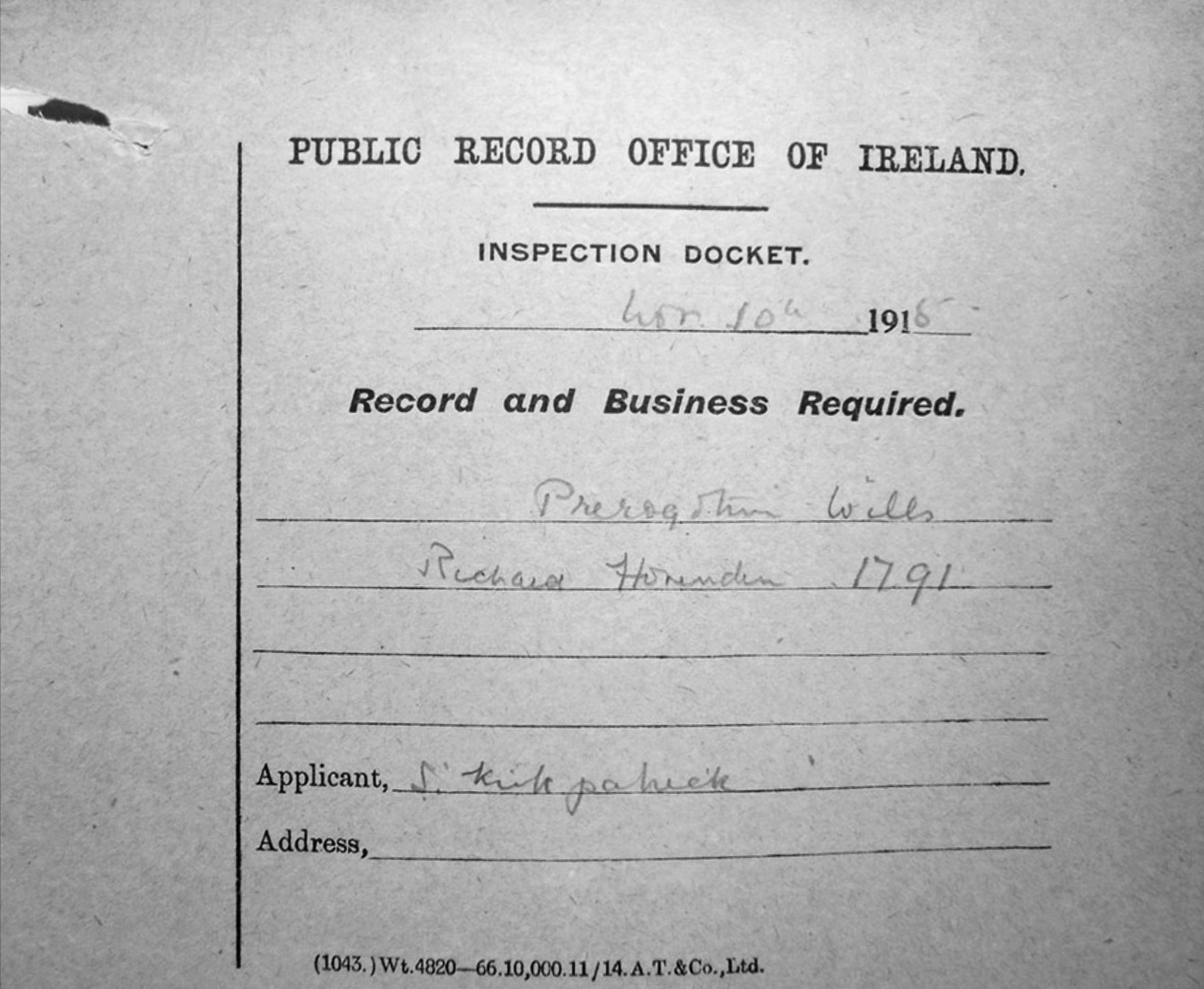

The discovery of a partial record of a fine, prompts me to think about the significance of a seemingly insignificant item and the profound narrative it contains. What transgression led to the fine being levied, and whose fine was it? Who decided that a law had been broken and how and why had that law been made?

A Consensus

Finding a reference book from 1830 detailing the rules and regulations of Customs and Tolls across Ireland, I am struck by the perfunctory listed content's poetic resonance. Each entry vividly depicts what was being sold at specific markets and what taxes were owed to the land owners who owned the land where the markets where held. Reading through the inventory of tariffs per item, I see the scene in front of me, the make-shift stalls, the smell and noise of the animals, the wind and the rain, the damp clothes, the raised voices and on it goes evoking a memory of something I read in a John Berger's essay,

"History is often hidden. It has to be re-found without being simplified. Today we talk about history as if it will give us the answers. But we also have to look at what has been forgotten, that which held the hopes and dreams of people because those hopes generated actions and sacrifices and that existed even if those hopes were illusory”

In the Virtual Record Treasury, I can see that every search transcends its data, evolving into visceral sensations and emotions. Experimenting with searches for terms like 'snow' and 'damp,' or ‘bark’ or ‘clap’, I assemble a tapestry of images and sounds, each fragment weaving distinct yet interconnected stories through time.

During the research period, before embarking on making Acts of Memory, a new perspective opens up that ultimately guides me towards what I see as a non-hierarchical approach to navigating archival material, and a non-hierarchical approach to making a film about the archive. I hope that others will follow to find their own way to this inspirational resource for their own creative endeavours.

Original text and images © Mairéad McClean 2024

Archive sources:

Fragment of a fine from the PROI fire of 1922 © National Archives Ireland.

An Introduction to the Knowledge of Maps: William Sharman, L0971 © Dublin City Library, Ireland

From a copy of a survey by Henry Pratt (1697) of the estate of Thomas Fitzmaurice, Lord Kerry, in the baronies of Clanmaurice, Iraghticonnor and Trughanacmy, County Kerry [UUC-U-121-1] Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland.

Damaged book from the PROI fire of 1922 © National Archives Ireland.

With special thanks to:

Trinity Long Room Hub Staff

The Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland Team

The Conservators and staff at The National Archives of Ireland, The Public Records Office Northern Ireland and The UK National Archives.

The year as Artist in Residence was funded by the Irish Government through the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media

The film Acts of Memory was project funded by the Arts Council of Ireland /an Chomhairle Ealaíon.

____________

*Excerpt from ‘Into the Archive: Writing and Power in Colonial Peru’ (Durham, NC, 2010) © Katy Burns, 2010.